Recidivism Rates Throughout America

Recidivism rates represent the period of time in which an incarcerated citizen is released from prison to the time they are re-incarcerated. These rates can vary greatly for each of the fifty states for a number of reasons, such as state legislation, population size, and the average amount of time in which a released incarcerated citizen returns to prison. Each state can differ on the measurements of years for recidivism, often between a 3-year period or 5-year period. In the state of Michigan, recidivism rates are determined based on a 3-year period. For example, in 2021, Michigan recidivism rate was reported as 26.7%, which is a sign that it continues to decrease compared to previous years (Gautz, 2021). Key characteristic factors have been identified in increasing a person’s likelihood of recidivism, such as age, gender, ethnicity, or education level.

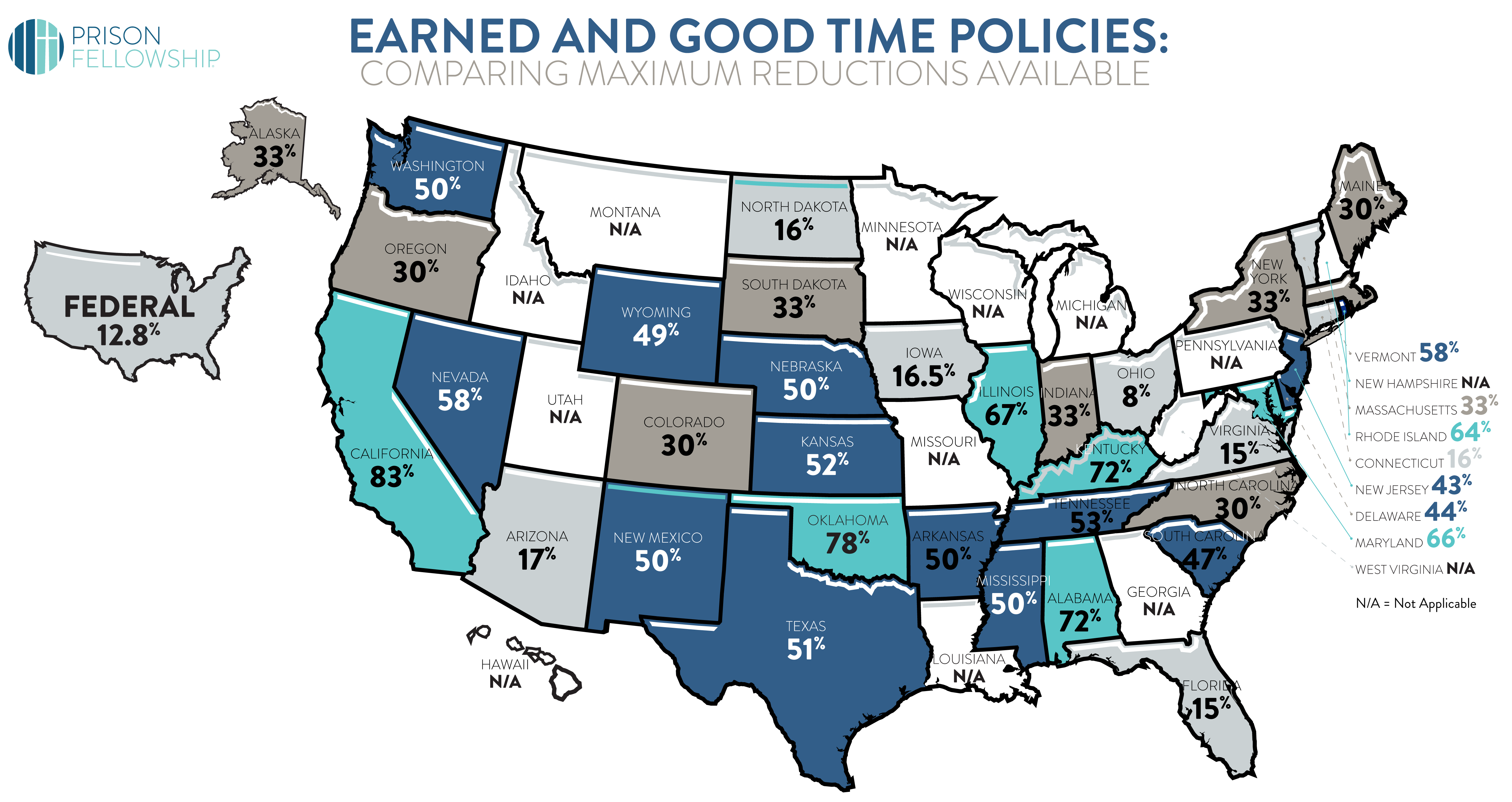

The terms for which each state uses in order to measure their recidivism rates can be determined based on whether a former incarcerated citizen is returned to prison for committing a new crime, re-offending for the original incarcerating crime, or violating their parole agreement. It is important for each state to have an understanding on their prisons’ recidivism rates. This allows for proper allocation of funding towards prison education, vocational, or treatment-based programs offered to incarcerated citizens. Depending on each state’s laws regarding Time- Served, incarcerated citizens can receive time credited towards the sentence for their participation in prison reform programs.

The top ten states with the highest population size are California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, and Michigan. Of these ten states with the largest populations, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and California had the highest recidivism rates, reporting between 50-53% of incarcerated citizens return to prison. The top ten states with the smallest population sizes include Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, Rhode Island, Montana, and Maine. Of these ten smallest population size states, the three with the highest number of returned incarcerated citizens are Alaska (66%), Delaware (65%), and Rhode Island (50%).

Based on a literature review of academic journal articles on each states’ recidivism rate, certain demographic factors were continuously identified as increasing a person’s chances of going back to prison after release. These factors included were if an incarcerated citizen is male, younger in age, and is a minority. Studies conducted by: Jones & Ross (1997), Spohn & Holleran (2002), Kubrin & Stewart (2006), Rubin and Doddge (2009), Hipp et al. (2010), Stahler et al (2013), Lee & Sanchez (2015), and Moore and Eikenberry (2021), all found similar findings. Additional factors were identified such as, failure to complete high school also led to higher recidivism rates (Lockwood et al, 2012). Continual post-release support and planning, as well as prison education courses (Thomas, 2014), employment assistance (Harm & Phillips, 2008), substance-abuse and mental health treatment, and housing plans were shown to reduce overall recidivism rates.

The rates of recidivism can shift among each state depending on a number of factors. Through the use of the collection of recidivism data for each of the states, consideration can be taken to determine the best course of action to not only reduce recidivism, but to address key needs that incarcerated citizens face when re-entering society. These range from academic resources to complete high school or a college education, finding employment that hires former- incarcerated citizens, addressing housing and basic care needs after incarceration, and finding treatment for substance or mental health issues.

Work Cited

Gautz, C. (2021, February 16). Michigan Department of Corrections: News & Publications press releases. Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://www.michigan.gov/corrections/0,4551,7- 119-1441_26969-520803–,00.html

Harm, N. J. PhD & Phillips, S. D. (2001) You Can’t Go Home Again,

Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 32:3, 3-21, DOI: 10.1300/J076v32n03_02

Hipp, J. R., Petersilia, J., & Turner, S. (2010). Parolee recidivism in California: The effect of Neighborhood context and social service Agency Characteristics*. Criminology, 48(4), 947-979. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00209.x

Jones, M., & Ross, D. L. (1997). Is less better?: Boot camp, regular probation And Rearrest in North Carolina. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 21(2), 147-161. doi:10.1007/bf02887447

Kubrin, C. E., & Stewart, E. A. (2006). Predicting who reoffends: The neglected role of neighborhood context in recidivism studies*. Criminology, 44(1), 165-197. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00046.x

Lockwood, S., Nally, J. M., Ho, T., & Knutson, K. (2012). The effect of CORRECTIONAL education On postrelease employment and recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 58(3), 380- 396. doi:10.1177/0011128712441695

Rubin, Mark and Dodge, Jennifer, “Probation in Maine: Setting the Baseline” (2009). Justice Policy. 25.

Sanchez, Matheson and Lee, Gang (2015) “Race, Gender, and Program Type as Predictive Risk Factors of Recidivism for Juvenile Offenders in Georgia,” The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 1.

Spohn, C., & Holleran, D. (2002). The effect of imprisonment on recidivism rates of felony offenders: A focus on drug offenders*. Criminology, 40(2), 329-358. doi:10.1111/j.1745- 9125.2002.tb00959.x

Tewksbury, R., & Jennings, W. G. (2010). Assessing the impact of sex offender registration and community notification on sex-offending trajectories. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(5), 570-582. doi:10.1177/0093854810363570

Thomas, S. L. (2014, August 01). Correctional curriculum evaluation: An uncovering of effective practices that reduce the rate of prison recidivism in the state of Alabama [Scholarly project]. In Northeastern University. Retrieved April 02, 2021, from http://hdl.handle.net/2047/d20018705

Tewksbury, R., & Jennings, W. G. (2010). Assessing the impact of sex offender registration and community notification on sex-offending trajectories. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(5), 570-582. doi:10.1177/0093854810363570