By Jordan Christian

California’s correctional officers are regularly exposed to traumatic events that make them more likely to grapple with depression, PTSD and suicidal thoughts, according to Officer Health and Wellness, a study done by Dr. Amy E. Lerman, a professor of public policy and political science, from the University of California, Berkeley. The report is based on the 2017 California Correctional Officer Survey (CCOS) on Health and Wellness, a large-scale effort to gather individual-level information on the thoughts, attitudes and experiences of a sample of 8,334 criminal justice personnel, which included prison guards and parole officers.

The report summarizes the results of the CCOS across a set of broad categories: mental and physical wellness; exposure to violence; attitudes towards rehabilitation and punishment; job training and management; work-life balance; and training and support. It also documents the difficulties of encouraging law enforcement personnel to seek the assistance they need.

Highlights of the findings include:

- Officers are exposed to violence at very high levels. More than half of correctional officers report that violent incidents are a regular occurrence at the prison where they work. Almost 30% reported being seriously injured at work, and 85 percent reported seeing someone seriously injured or killed.

- Work-related stress has significant health consequences. 50% of officers say they rarely feel safe at work, and officers who don’t feel safe at work are more likely to report headaches, digestive issues, high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease than other correctional officers.

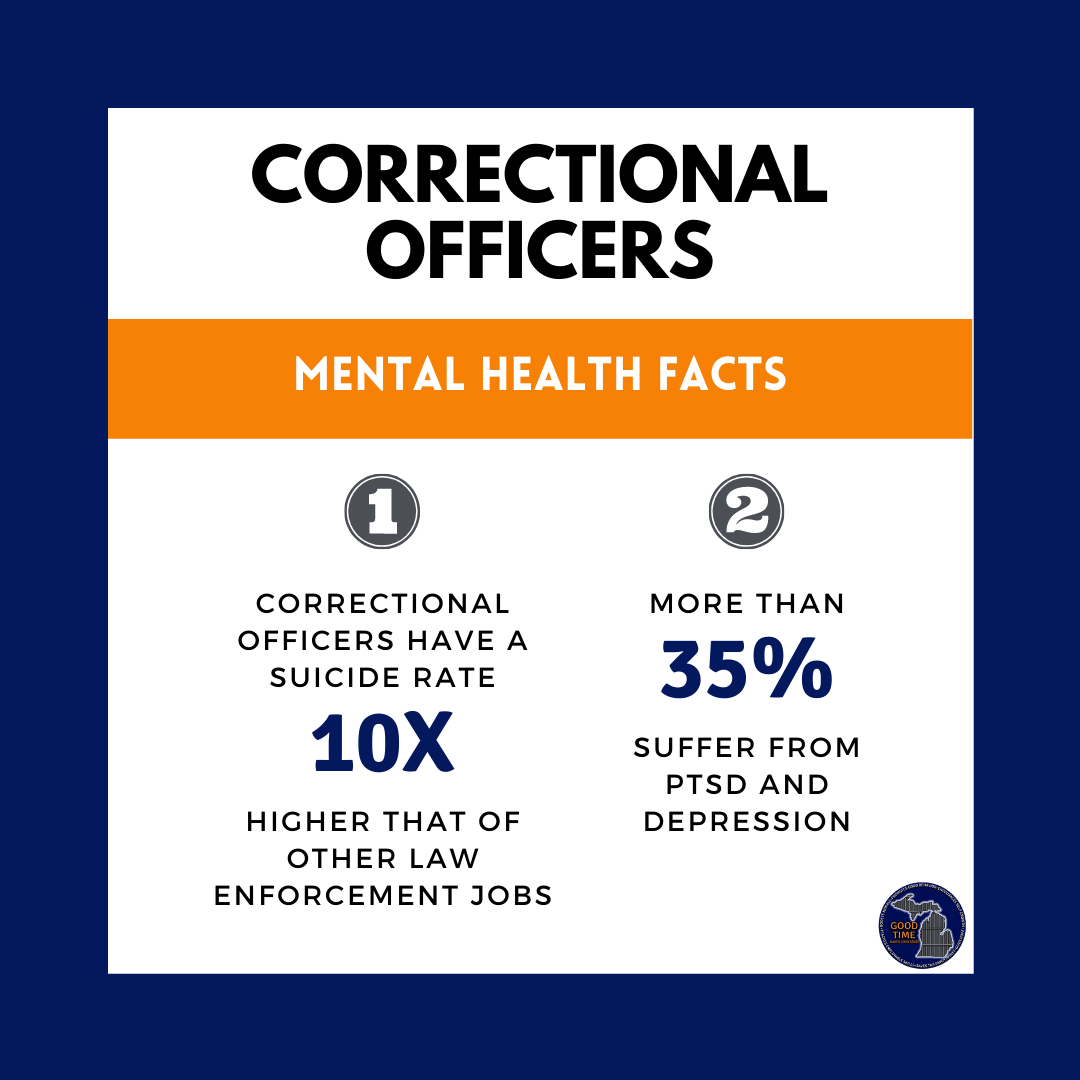

- Depression is a way of life for many law enforcement personnel. More than one-third of officers report that someone in their lives has told them they have become more anxious or depressed since they started working in corrections. 28% report often or sometimes feeling down, depressed or hopeless, and 38% have little interest or pleasure in doing things.

- 1 in 3 have experienced at least one symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, 40% of officers report that they have experienced an event so frightening, horrible or upsetting at work that they have had nightmares about it.

- 10% of correctional officers have thought about killing themselves. The rate of suicidal thoughts is even higher for retired correctional officers (1 in 7). Of those who say they have thought about suicide, 31% report thinking about it often or sometimes in the past year. More than 7 in 10 haven’t told anyone, meaning that many are suffering in silence.

- Only a minority of officers say they have ever used the state-sponsored programs meant to improve their well-being. For example, only 18% reported ever having used the Employee Assistance Program (EAP), and only 3 percent say they have made use of the Peer Support Volunteer program. Many officers said they were worried about privacy: One-fifth of correctional officers say they worry about repercussions if they were to reach out to EAP for help with work-related mental health issues.

(The link to study results can be found here.)

A Phenomenological Study of Correctional Officers’ Perceived Emotions on the Job

This study/dissertation was done by Heather S. Grammatico from Walden University in 2017. Their purpose of the study was to explore the emotions experienced by correctional officers while at work in a prison setting. They designed this study:

- “to address the emotional component of working in a prison”

- “to allow the participants the opportunity to address the various emotions felt throughout a shift”

- “to offer participants the opportunity to discuss if they feel that they can express the felt emotions while at work”

For this study, Grammatico used a 15-item open-ended questionnaire accessible through the website Survey Monkey. These questions were:

- When you arrive on the institution grounds, what is the first emotion you are aware of feeling?

- During your shift, when you interact with an inmate, what emotion are you aware of feeling?

- When there is a violent incident that you are involved in, or witness to, what emotion are you aware of feeling?

- When you interact with staff at the management level, do you have any specific emotions?

- Overall, when you are inside the institution interacting with coworkers, inmates, and management, what are the most consistent emotions you are experiencing?

- Are there certain incidents where you feel one emotion, yet express another?

- If you express an emotion different than the one you are feeling, why do you think you might do that?

- In the event of a violent incident in which an inmate may be seriously injured or killed, what emotions do you feel?

- Do you discuss emotions regarding the job with coworkers while on the job?

- Do you feel that the emotions you express (externally) while on the job are consistent with what you are feeling (internally), or do you alter what you exhibit/show coworkers?

- When you leave the institution, how do you process the day’s events?

- Do you discuss the emotions you feel during the day with family or friends?

- Explain what emotions you feel when faced with a tense situation at home.

- Do you express the emotions you feel in personal situations or doyou feel one emotion but exhibit another?

- Do you think that the emotions you exhibit in your personal life are appropriate for the situation?

Each of the corresponding answers were color coded, matching a specific answer but none of the answers were worded in a way that would lead a participant in a certain direction.

The intended recipients were correctional officers, sergeants, lieutenants, and captains working in any California correctional facility. This questionnaire was distributed anonymously among the participants using the snowball sampling technique, where existing study subjects recruit future subjects from among their acquaintances. The initial participants were given the option of either completing the questionnaire or not and passing the introduction, consent form, and link on to the next person who met the criteria. Grammatico had no knowledge of whether the initial participants had completed the survey.

The results of their study showed that correctional officers felt a high amount of anxiety while on shift and during their time with other staff as well as inmates. Another of their findings showed that the correctional staff expressed emotions that they did not feel at the time and were also uncomfortable showing and talking about their emotions at work. Lastly, Grammatico found that correctional staff brought their work attitudes outside of work either did not show emotion or showed the incorrect emotion for the situation they were in.

(The link to this study can be found here.)

Descriptive Study of Michigan Department of

Corrections Staff Well-being: Contributing

Factors, Outcomes, and Actionable Solutions

This study was done by doctors Caterina Spinaris and Nicole Brocato of the Desert Waters Correctional Outreach and Gallium Social Sciences in 2019. Their purpose was to improve the Michigan Department of Corrections’ ability to support their employee’s well-being. During the study, they focused on a set of “outcomes” indicative of employee well-being: those being physical health, mental health, family health, work health, and social health.

They examined the data of 3,502 participants across 8 employee working groups:

- Custody staff (women’s facility)

- Non-custody staff (women’s facility)

- Custody staff (all other facilities)

- Non-custody staff (all other facilities)

- Field operations administration (Parole and probation agents and absconder recovery unit investigators)

- Field operations administration (all other staff)

- Headquarters (managers/supervisors)

- Headquarters (all other staff)

Their general findings, in terms of outcomes, showed that physical, mental, and family health are highly impacted by work health rather than traumatic events, meaning that the quality of the work environment has a much greater effect on mental, physical, and family health than does exposure to trauma or danger. Social health, which they defined as the quality of relationships with supervisors, coworkers, and offenders, is tied to work health. So as social health improves, so does work health. These health outcomes work in a domino effect that depends on the quality of social health.

In their more specific findings, they gathered disorder rates for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety, PTSD, suicidal ideation, and alcohol abuse using the clinical scoring criteria of what they described as valid screening instruments.

(It was noted that these instruments were not sufficient to provide a formal diagnosis and could only determine whether people have a certain number of symptoms consistent with said disorder. A formal diagnosis required completion by a licensed behavioral or medical health professional.)

The following are their findings using weighted survey statistics:

Around 1 in 6 of all MDOC employees met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder. When they looked at the rates through the 8 groups that they were examining, about 1 in 4 of custody employees working at male facilities, and about 1 in 8 support staff in headquarters (i.e., not managers), met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder.

Around 1 in 2 of all MDOC employees scored in the medium to high range for Generalized Anxiety. This rate was 16 times the national average at the time.

Nearly 1 in 4 of all MDOC employees met criteria for PTSD, with 41% of custody staff working at male facilities meeting criteria for PTSD. The rates of PTSD at MDOC were nearly 7 times higher than the national average in the general population.

Nearly 1 in 5 of all MDOC employees met criteria for alcohol abuse, with 1 in 4 of custody staff working at male facilities and about 1 in 6 managers/supervisors in headquarters met criteria for alcohol abuse. (The national rate of alcohol abuse in the general population in 2019 was estimated to be 7%, making MDOC’s overall rate 2.7 times higher than the national average.)

The weighted survey they used indicated that around 1 in 11 (9%) of all MDOC

employees reported scores “indicative of suicidal ideation“, and “a need for immediate mental health support.” And they also found that a total of 34 surveyed individuals reported they were actively planning to complete suicide.

(The link to the full study can be found here.)